Biography courtesy of New Georgia Encyclopedia:

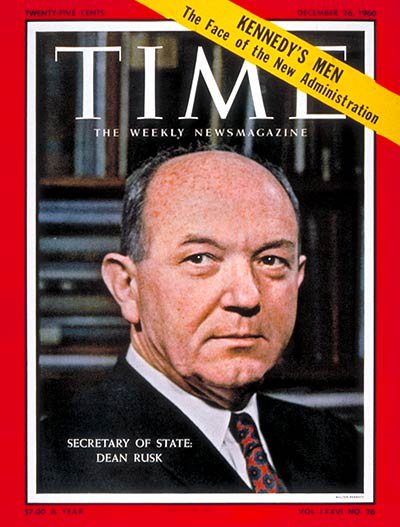

David Dean Rusk (1909 - 1994) served as U.S. secretary of state from 1961 to 1969, the second longest tenure in that office (after Cordell Hull, 1933-44). He was only the second Georgian to be named to the office. During that period of service under U.S. presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, he was a primary architect of U.S. intervention in the Vietnam War (1964-73) on the side of the South Vietnamese. He was known, too, for his dedication to arms control negotiations with the Soviet Union and other early manifestations of détente, as well as for his skill in seeking a diplomatic resolution to the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

Early Life

David Dean Rusk was born on February 9, 1909, in Cherokee County, and attended Lee Street Elementary and Boys High School in Atlanta. In 1931 he earned an A.B. degree from Davidson College in North Carolina, where he was a standout in the classroom and as a center on the basketball team. He subsequently attended England’s Oxford University on a Rhodes scholarship, earning B.S. and M.A. degrees from St. John’s College in 1933 and 1934.

While at Oxford Rusk stood at the back of the room observing when members of the Oxford Union debate society cast their votes overwhelmingly in favor of a policy of appeasement toward Nazi Germany. He believed at the time that this vote was wrong-minded, because he felt that dictators like Adolf Hitler could not be appeased. He was soon proven right as Hitler set out to expand the Third Reich through the threat and use of military force, which led to World War II (1941-45). The experience had a profound effect on Rusk’s worldview and would make him a determined opponent of efforts to meet acts of aggression with offers of appeasement. During events leading to the war in Vietnam, he counseled President Johnson strongly against a policy of yielding to Communist forces in Indochina.

Upon returning to the United States, Rusk accepted the post of associate professor of government and dean of faculty at Mills College in Oakland, California, where his academic specialty was international relations. He remained at Mills for six years (1934-40) and also studied law during this period at the University of California, Berkeley (though he did not complete a degree). At Mills he met a student by the name of Virginia Foisie. They married in 1937 and had three children: David Patrick, Richard Geary, and Margaret (Peggy) Elizabeth. David Rusk grew up to serve as mayor of Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Richard Rusk coauthored with his father a memoir entitled As I Saw It (1990).

Early Government Service

With the United States’ entry into World War II on the horizon, Rusk joined the U.S. Army in 1940, serving first with the Third Infantry Division, then in the Military Intelligence Service. He served from 1943 to 1945 in the China-Burma-India theater, where he began a lifelong interest in Asian affairs. Achieving the rank of colonel at the end of the war, Rusk joined the general staff in the War Department in Washington, D.C. There he had the opportunity to work with General George Marshall, who would soon become secretary of state and author of the Marshall Plan to assist the war-wrecked nations of Europe.

Rusk was initially intent on carrying forward his military career, until Secretary Marshall asked him in 1947 to head the Office of Special Political Affairs (“also known as the U.N. desk,” as Rusk says in his memoirs) in the Department of State. In that capacity he privately advocated Marshall’s view opposing the establishment of an independent state of Israel; but when U.S. president Harry S. Truman decided in favor of an Israeli state, Rusk loyally backed the president, believing (as did Marshall) that once a president makes a decision, staff should either support it or resign.

In 1950 U.S. policy toward Asia became increasingly controversial and partisan in Washington, as Republican lawmakers pointed a finger at the Truman administration for mishandling policy in that region—first by “losing” China to the Communists in 1949 and then by failing to thwart an invasion of South Korea by North Korean Communists. Secretary of State Dean Acheson was grateful when Rusk volunteered to help him counter the Republican criticism. Acheson appointed him in 1950 as assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs. Remaining consistent in his anti-appeasement views, Rusk joined Acheson and others in urging President Truman to resist Communist aggression on the Korean peninsula.

In 1952 Rusk left government service to become president of the Rockefeller Foundation, where he focused on development programs for poor nations as well as the dangers of environmental pollution from the testing of nuclear bombs in the atmosphere. In 1960 he published an essay in Foreign Affairs exalting the role of the president in foreign policy. The piececaught the eye of Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy. When elected president a few months later, Kennedy had Rusk on his mind because of this article; moreover, Rusk came strongly recommended as a candidate for secretary of state by Acheson, among others, who spoke of his unwavering loyalty and willingness to take the heat on Truman policies toward Asia.

Secretary of State

President Kennedy chose Rusk as secretary of state in 1961, although (as it turned out) he would rely more on his national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy,for day-to-day foreign policy guidance. After Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 Rusk continued on as secretary of state for President Lyndon Johnson. Both Johnson and Rusk came from simple, rural backgrounds, and Rusk enjoyed a much closer and more influential relationship with Johnson than he had with Johnson’s affluent Bostonian predecessor.

During the Kennedy administration the young president and his secretary of state found themselves tested very quickly, as the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) paramilitary operation against Cuba failed disastrously in April 1961. Rusk had personally disapproved of the operation, but ultimately supported it as a means to achieve the president’s wish to rid the world of the Castro dictatorship on the island. As the operation met fierce resistance by the Cuban military, some in the administration argued on behalf of U.S. air support. Rusk firmly opposed overt intervention by the air force and so counseled the president, who followed his advice. The CIA’s paramilitary operatives, mainly Cuban exiles, were decimated by Cuban defenders on the beaches at the Bay of Pigs.

In October 1962 reconnaissance overflights by the CIA’s U-2 spy planes discovered the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba. Rusk recommended a tough diplomatic response but resisted proposals from the U.S. military to invade Cuba. Rusk’s most important contribution as secretary of state was to provide calming counsel to the president against the precipitous use of armed force and to employ skillful behind-the-scenes diplomacy with Soviet officials to have the missiles removed. He helped convince the president to forgo an immediate attack against Cuba and instead to establish a “quarantine” (blockade) against Soviet ships bringing more missiles to Cuba. This would provide the president and the Department of State with more time to work out a diplomatic resolution.

Another prominent achievement of Secretary Rusk was the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, in which the Soviet Union and the United States agreed to halt above-ground testing of bombs, which contaminated the atmosphere with substantial quantities of radioactive material. He also championed increased developmental aid to poor nations in Africa and Latin America. More controversially, he supported a CIA coup in Congo, argued against the imposition of sanctions to end apartheid in South Africa (although he opposed the practice of apartheid itself), and despite misgivings, never attempted to dissuade President Johnson against deployment of the U.S. Marines to quell unrest in the Dominican Republic in 1965.

The Vietnam War dominated the later years of Rusk’s term as secretary. He was wary, on the one hand, of escalating the war to a point where the Chinese might feel compelled to intervene, as they had during the war in Korea (1950-53); on the other hand, his anti-appeasement philosophy recoiled at the notion of standing on the sidelines as Communist forces from North Vietnam, armed by the Soviets and Chinese, sought to overrun South Vietnam. Predictably, Rusk tilted toward escalation of the war to halt the Communists and prevent the falling of “dominoes” throughout Asia. He became an articulate proponent of the war and, at the same time, a villainous figure on American college campuses, where the wisdom of American involvement was widely—and sometimes violently—questioned. The war ended in a humiliating defeat for the United States and the loss of more than 58,000 troops.

When Richard Nixon won the U.S. presidency in 1969, Rusk left the Department of State and returned to Georgia, where he taught international law at the University of Georgia in Athens. Uninterested in the pursuit of lucrative lecture fees or book contracts, he led a quiet life at the university—though he was always available on campus to spend time with anyone, from the lowliest first-year student to the most distinguished professor, who might drop by his office to discuss history and current affairs. Once vilified by students around the country and by his own colleagues in Washington who had turned against the war in Vietnam (as he never did), Rusk spent his final years much admired and respected in the university and the town of Athens. He died in Athens of congestive heart failure on December 20, 1994, and is buried at Oconee Hill Cemetery.

In 1977 the university established the Dean Rusk Center for International Law and Policy, which provides interdisciplinary study and service opportunities for law students and faculty. In 1985 Davidson College established the Dean Rusk International Studies Program in honor of one of its most distinguished alumni. Dean Rusk Middle School in Canton is also named in his honor.

- Johnson, Loch. "Dean Rusk." New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Dec 10, 2019. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/dean-rusk-1909-1994/